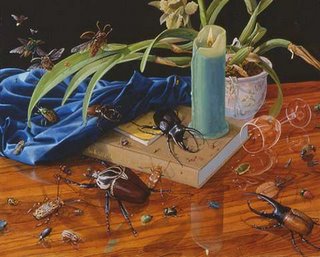

MAN TO MANTIS

The first Praying Mantis (Mantis religiosa) of the year perches on my weathered redwood fence. Barely a quarter of an inch long, his normally cryptic straw coloring stands out on the dark wood. A few days ago he and a couple hundred siblings squirmed free of their egg case, or ootheca. Very few of them will survive the summer. Chances are good that a sibling served as this little fellow's first meal, and most of those who don't fall to cannibalism will nourish some other creature in the coming months. Over the summer, the survivors will grow to a length upwards of three inches. The adult males, who fly well, are likely to wander further than their larger sisters before mating. The females of many spiders, scorpions, midges, and other arthropods enjoy their mates as post-nuptial dinners, but this behavior is most famous among the mantids. Allusions to the deadly mantis mate abound in legend and literature worldwide. One of the many colorful historical rulers of Madagascar is remembered as “The Mantis Queen.” Her henchmen were required to bring her handsome young men, then to toss them over a cliff once she was through with them.

The first Praying Mantis (Mantis religiosa) of the year perches on my weathered redwood fence. Barely a quarter of an inch long, his normally cryptic straw coloring stands out on the dark wood. A few days ago he and a couple hundred siblings squirmed free of their egg case, or ootheca. Very few of them will survive the summer. Chances are good that a sibling served as this little fellow's first meal, and most of those who don't fall to cannibalism will nourish some other creature in the coming months. Over the summer, the survivors will grow to a length upwards of three inches. The adult males, who fly well, are likely to wander further than their larger sisters before mating. The females of many spiders, scorpions, midges, and other arthropods enjoy their mates as post-nuptial dinners, but this behavior is most famous among the mantids. Allusions to the deadly mantis mate abound in legend and literature worldwide. One of the many colorful historical rulers of Madagascar is remembered as “The Mantis Queen.” Her henchmen were required to bring her handsome young men, then to toss them over a cliff once she was through with them.It's common for a male Praying Mantis to lose his head when mating, and counterintuitively enough, it seems that there's a benefit in this. Not only does his sacrifice help to nourish the growing embryos of his offspring, but once his cerebral fear center is gone, his focus on the task at hand is more complete; headless mantises produce more sperm. Once fertilized, the female will carry her eggs for a month or more before laying them within a foamy, meringue-like secretion that hardens quickly into the ootheca. All the adults will die by first frost, but the oothecae will overwinter to begin the cycle anew in the spring.

Most summers I find myself taking an adult Praying Mantis captive. I never tire of watching them; their erect posture and mobile head with two large eyes give them an uncommon look of intelligence, and their rapacious nature is really fun to watch. They often tackle amazing quarry. A biologist friend told me of a mantis at a friend's ranch in Colombia that captured bats as they emerged from their daytime roosts in pockets of a woven palm ceiling. Unable to spread their wings, they could do nothing but accommodate the insect, who ate until sated, then moved on, leaving a tiny, faceless corpse to drop onto the dining table.

Most summers I find myself taking an adult Praying Mantis captive. I never tire of watching them; their erect posture and mobile head with two large eyes give them an uncommon look of intelligence, and their rapacious nature is really fun to watch. They often tackle amazing quarry. A biologist friend told me of a mantis at a friend's ranch in Colombia that captured bats as they emerged from their daytime roosts in pockets of a woven palm ceiling. Unable to spread their wings, they could do nothing but accommodate the insect, who ate until sated, then moved on, leaving a tiny, faceless corpse to drop onto the dining table.M. religiosa was introduced to North America accidentally at the end of the 19th century, and spread through most of the continent within a hundred years. As a boy, I tried twice to introduce them into our yard, but to no avail—both efforts were immediately frustrated by paper wasps (Polistes sp.), which consistently found and ate them within minutes. The first mantis I ever saw, though, was a native ground mantid (Litaneutria sp.) that I caught beneath a Curlyleaf Mountain Mahogany (Cercocarpus ledifolius) when I was about seven. An inch or so in length, it resembled nothing more than a gray mahogany twig. Never again have I seen one of these insects, though I've spent untold hours in such habitat—their amazingly cryptic appearance all but rules out their discovery. Children are much better than adults at finding insects, anyway. Having a head that's built more than twice as close to the ground helps a lot.

_____________________

upper: MALAYSIAN PEACOCK MANTIS (2005) acrylio 11" X 6"

lower: COSTA RICAN SCRUB MANTIS ( 1998) acrylic 51/2" x 4"