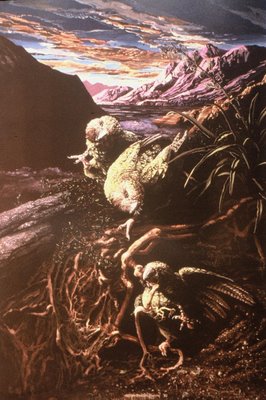

Several readers have suggested a post about my painting technique, and, ever the full-service blogger/confirmed pushover, I've chronicled my procedure on this recent acrylic painting, one of a series of commissions for "Vanishing Circles," a collection of artwork being assembled for the

Arizona/Sonora Desert Museum depicting endangered flora and fauna of the region. The subject here is a Desert Tortoise (

Gopherus agassizi). All of these images may be clicked on for closer scrutiny.

Step one is executing a drawing - something I'm not terribly skilled at. I know a number of artists who can draw something worthy of Abrecht Dürer in a few short minutes. I'm not among them. I have to plan everything out. A drawing starts with a number of little thumbnail sketches, slowly refining things until I get something I'm happy with. A tortoise is an easy animal to draw, and this drawing was simple and straightforward. With a trickier subject, it's common for me to waste half a dozen sheets of paper refining thumbnails to figure out how to draw a single element.

Once I've worked out how to draw the main subject, I put together a composition drawing. Here I've positioned a male Desert Tortoise preparing to charge an opponent. Our hero's head, where all the intent of the piece will lie, is centered on the page. His body occupies the upper-right quarter of the composition. A hedgehog cactus (

Echinocereus sp.) behind him adds mass to that quandrant, suggesting an impending charge from the corner, diffusing that mass into the relative empty space before it. The dark carapace in the opposite corner creates a tension between the two animals, and a stick marks the protagonist's future trajectory. The actual "runway" will be fairly free of stones to add to the effect.

The finished drawing is 10" x 15", one-half the dimensions of the finished painting. The drawing is Xeroxed at 200%, and traced onto a 20" x 30" sheet of Strathmore cold-pressed illustration board. I use a fine red ball-point pen to do the tracing, so I can tell where I've been. In this photo, the seams of four different Xerox sheets can be seen.

My approach to painting in acrylics is completely dependent on watercolor techniques. I never paint with anything thicker than ½ paint and ½ water. Logically, I use watercolor brushes: round sables and mops. My finest detail brush is a 00 rigger. My biggest brush is a 1½" squirrel mop. I prefer long-bristled brushes that I can load up with a lot of paint.

Using the 00 riggers, I paint a detailed underpainting in raw umber. The main objective here is to establish the forms and the textures. I use a Windsor & Newton series 530. This is my primary working brush, hence the term "rigger vitae." One of them lasts an average of about four days.

The textures of the rocks will be established later, so they are left blank. The cactus is also only described by outlines of the bodies and length and direction of some of the spines. This is because the cactus bodies will not appear in the finished painting, only the dense spines will. The main purpose of the underpainting is to serve as a roadmap so I can keep track of the shapes and textures while focussing on other matters, like lighting and color theory. The finished underpainting is tinted with glazes of thin paint. I want this piece to look hot and dry, so the tint is of earth tones composed of large quantities of cadmium orange, a very warm color.

The colors and values of the main subject are established.

The subject is masked off, using light card stock and liquid latex.

I begin painting the background, putting tiny highlights on dirt granules.

The cactus bodies are painted, using the darkest values that will appear in the finished piece. I begin to paint the darkest, least illuminated spines, and successively paint lighter and lighter spines on top of those.

Once the background is established, I remove the mask from the subject, and begin to work on the piece as a cohesive whole.

The shapes, textures and values are all securely on the board at this point. I continue to give depth to the piece by pushing back some parts, pulling others forward, using color temperature and value. I also continually enrich the colors with successive glazes.

Here, the tortoise has received a rich brown glaze. The cactus is beginning to take shape as lighter-colored spines are added.

Detail is added to the dirt to give it shape, and the same thing is done for the tortoise.

The finished piece, with such details as a gray hairstreak butterfly (

Strymon sp.) and a honey ant (

Myrmecocystus sp.).

When I first heard the music of Gogol Bordello, a couple of years ago, I made myself a promise. "Carel," I said, "If this band comes within 100 miles of you, I'm gonna take you to see them". Well, tonight's the big night, and the drive to Park City is a mere dozen miles. Their most recent cd is titled Gypsy Punks, and that's a fairly apt description of their music. Fronted by the crazed and charismatic Ukrainian emigré Eugene Hütz, the band's catchy minor-key melodies often evoke the Hot Club of Paris, while their furious rhythm section adds a post-punk aggression to the mix. Hütz plays rhythm guitar and sings...well, you can't really call it singing, but whatever it is, it's absolutely compelling. His lyrics (in English, often slipping into Ukrainian, Spanish, Italian, or languages known only to the ancients) are at once engaging, literate, amusing, and totally incomprehensible. Of equal importance is the versatile violin of Sergey Ryabtzev. At one moment he'll play in the sweet, lilting style of Stéphane Grapelli, the next in a gritty, scraping manner suitable for a Romani campfire, then suddenly shift into a more mainstream tone that Borodin or Khatchaturian might demand.

When I first heard the music of Gogol Bordello, a couple of years ago, I made myself a promise. "Carel," I said, "If this band comes within 100 miles of you, I'm gonna take you to see them". Well, tonight's the big night, and the drive to Park City is a mere dozen miles. Their most recent cd is titled Gypsy Punks, and that's a fairly apt description of their music. Fronted by the crazed and charismatic Ukrainian emigré Eugene Hütz, the band's catchy minor-key melodies often evoke the Hot Club of Paris, while their furious rhythm section adds a post-punk aggression to the mix. Hütz plays rhythm guitar and sings...well, you can't really call it singing, but whatever it is, it's absolutely compelling. His lyrics (in English, often slipping into Ukrainian, Spanish, Italian, or languages known only to the ancients) are at once engaging, literate, amusing, and totally incomprehensible. Of equal importance is the versatile violin of Sergey Ryabtzev. At one moment he'll play in the sweet, lilting style of Stéphane Grapelli, the next in a gritty, scraping manner suitable for a Romani campfire, then suddenly shift into a more mainstream tone that Borodin or Khatchaturian might demand.