OF KAKAPO AND CONDORS

Around eight centuries ago, Polynesian sailors began to settle New Zealand. They were the first mammals to have ever set foot on the islands, save for three bat species, and their effect on the ecology was immediate. The lack of mammalian game was more than made up for with a rich bird fauna. Niches occupied elsewhere by mammals were exploited here by bird species, and without ground predators, many lost the ability to fly. The most spectacular of these flightless birds were the giant moa (order Dinornithoformes), huge, native ratite birds. All ten species of giant moa were hunted to extinction within a century. A smaller, fifty-pound species, Megalaperys didinus probably survived in remote mountains until the 17th century. These people, the ancestors of today's Maori, were soon joined on the islands by their commensal, the Polynesian Rat (Rattus exulans)and by domestic dogs (Canis familiaris). Ultimately, European sailors introduced more mammals into the mix, including House Cats (Felis cattus), Stoats (Mustela erminea), and their own species of ship rat, Rattus rattus. The collective mammalian armada wiped many New Zealand bird species right off the islands. By 1970 it was feared that this fate had reached one of the archipelago's most amazing birds.

Around eight centuries ago, Polynesian sailors began to settle New Zealand. They were the first mammals to have ever set foot on the islands, save for three bat species, and their effect on the ecology was immediate. The lack of mammalian game was more than made up for with a rich bird fauna. Niches occupied elsewhere by mammals were exploited here by bird species, and without ground predators, many lost the ability to fly. The most spectacular of these flightless birds were the giant moa (order Dinornithoformes), huge, native ratite birds. All ten species of giant moa were hunted to extinction within a century. A smaller, fifty-pound species, Megalaperys didinus probably survived in remote mountains until the 17th century. These people, the ancestors of today's Maori, were soon joined on the islands by their commensal, the Polynesian Rat (Rattus exulans)and by domestic dogs (Canis familiaris). Ultimately, European sailors introduced more mammals into the mix, including House Cats (Felis cattus), Stoats (Mustela erminea), and their own species of ship rat, Rattus rattus. The collective mammalian armada wiped many New Zealand bird species right off the islands. By 1970 it was feared that this fate had reached one of the archipelago's most amazing birds.The Kakapo (Strigops habroptilus) is unique among parrots. Nocturnal and virtually flightless, it is also the most massive psittacine bird, weighing as much as eight pounds. The males congregate to display in leks, much like some grouse species do. As the last of the Kakapo lay in peril of the ever-increasing Stoats, a restoration program was put into effect. This plan involved trapping the entire known population of about 50 individuals and transferring it to Maud Island, a small, predator-free island in the Marlborough Strait. This strategy was first used at the end of the 19th century, when reserve manager Richard Henry moved 200 Kakapo to Resolution Island, northwest of South Island. Within a few years, Stoats swam to Resolution Island and killed the entire population, and it didn't take them long to make the transit to Maud Island, either. A big part of the program has since consisted of moving the birds from one island to the next, always a half-step ahead of the rats and Stoats. For the past three years, the Kakapo have been transferred between two tiny islands, Chalky and Codfish. When trees are fruiting massively on one island, the birds are taken there, while predator control maintenance is effected on the other. Hen Kakapo normally lay eggs only in years of plentiful food, usually every three years or so. Once managers began augmenting the females' food supply, the birds laid every year, but with a strong bias toward producing male chicks. Females have since had their diets carefully monitored, to keep them at a weight where they will produce at maximum capacity, but with an even sex ratio. The current population of 86 birds is highly inbred—all but one of the original Maud Island birds came from Stewart Island. The single bird from the South island is a 50-ish year-old male named after Richard Henry. Artificial insemination has been used only recently to try to keep the gene pool as diverse as possible.

Meanwhile, on my side of the globe, a similar program has kept the California Condor (Gymnogyps californianus) from extinction. Relicts from the Pleistocene, when North America's fauna was rich with huge herbivores, the once plentiful condors mostly vanished once the Clovis culture extirpated the mega mammals. By the time Columbus set sail, condors only clung on in North America's southwestern tenth and in the rugged South American Andes. Although their distribution was limited, California Condors ranged widely. Under favorable circumstances, they could fly from California's Imperial Valley to the Columbia River in a day, and at the peak of the salmon runs, they would take full advantage. As the continent was developed, the vast open spaces the birds depended on dwindled. What large animal carcasses could be found were often tainted with lead bullets or by cyanide coyote traps. By 1985 a mere 27 birds remained, and the bold decision to take the entire population into captivity was taken.

Meanwhile, on my side of the globe, a similar program has kept the California Condor (Gymnogyps californianus) from extinction. Relicts from the Pleistocene, when North America's fauna was rich with huge herbivores, the once plentiful condors mostly vanished once the Clovis culture extirpated the mega mammals. By the time Columbus set sail, condors only clung on in North America's southwestern tenth and in the rugged South American Andes. Although their distribution was limited, California Condors ranged widely. Under favorable circumstances, they could fly from California's Imperial Valley to the Columbia River in a day, and at the peak of the salmon runs, they would take full advantage. As the continent was developed, the vast open spaces the birds depended on dwindled. What large animal carcasses could be found were often tainted with lead bullets or by cyanide coyote traps. By 1985 a mere 27 birds remained, and the bold decision to take the entire population into captivity was taken.Like Kakapo, wild California Condors do not usually produce every year. In captivity their eggs were whisked away to incubators, and the hens often laid replacement eggs. Captive propagation has been very successful, and in 1992 reintroduction began in California and Arizona. Today 127 condors live in the wild, including a wild-fledged four-year-old. 146 Condors are presently in captivity, including eleven that are being prepared for release. The bad news is that deaths, mostly from power line collisions and lead bullet ingestion, still far outnumber wild births. Practically all of the Arizona birds have had to be re-trapped for chelation therapy for lead poisoning. A number of behavioral problems, such as extreme tameness are being manifested, but it appears that California Condors will continue to wheel in the sky for some time to come.

Both of the species mentioned in this post are the equivalents of ICU patients, with EKGs monitored and tubes up their nares. They are in a state closer to captivity than wildness, and would collapse if we were not there to prop them in place. They have literally outlived their own homes. I'm fully in support of the Herculean measures being taken to keep the patients out of the grave; these are extraordinary birds, and losing them would be a human tragedy if not a natural one. But we should ask ourselves if this is the kind of natural world we want to leave for future generations. We can expect to see more of the kind of intensive management that takes place today on Codfish Island and the Vermilion Cliffs. The line between zoo and refuge is continually being smudged, and that's the biggest tragedy of all.

Both of the species mentioned in this post are the equivalents of ICU patients, with EKGs monitored and tubes up their nares. They are in a state closer to captivity than wildness, and would collapse if we were not there to prop them in place. They have literally outlived their own homes. I'm fully in support of the Herculean measures being taken to keep the patients out of the grave; these are extraordinary birds, and losing them would be a human tragedy if not a natural one. But we should ask ourselves if this is the kind of natural world we want to leave for future generations. We can expect to see more of the kind of intensive management that takes place today on Codfish Island and the Vermilion Cliffs. The line between zoo and refuge is continually being smudged, and that's the biggest tragedy of all.___________________

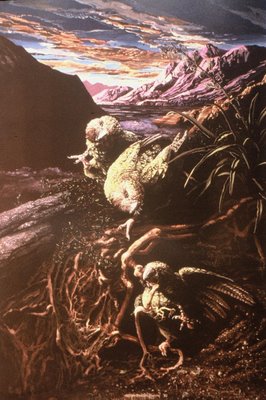

upper: KAKAPO--PARROTS OF THE NIGHT (1990) acrylic 30" x 20"

center: CALIFORNIA CONDOR (2005) oil ceiling mount 96" x 72"

lower: ANDEAN CONDORS & PATAGONIAN CONURES (1997) ACRYLIC 20" X 30"

10 Comments:

Carel, yet another great post. I was fortunate enough to see a couple of the Vermillion Cliffs Condors when they were hanging out at the South Rim of the Grand Canyon (presumably snacking on yummy tourist trash). At a distance, it took me a few seconds to figure out why those huge eagles had white stripes on their wings.

Some friends of mine worked on this stable isotope study which suggests coastal Condors survived the extinction of the Pleistocene megafauna by snacking on marine mammals. Declining marine mammal populations in the 19th and 20th centuries probably played a role in the California Condor's close brush with extinction. Great science and it raises some potentially interesting implications for Condor population management too.

I wouldn't raze that shabby old stone calendar in Salisbury or the half-demolished party hall in Rome . Likewise I'm glad these birds are still hanging on despite their apparent evolutionary obsolescence. Perhaps we can hope that things like habitat preservation and control of invasive non-natives reduce the need for this kind of desperate, against-all-odds approach to conservation.

For more on relict species Ghosts of Evolution is a good place to go. Great reading for anyone who has looked at an avocado pit and wondered what lucky species was supposed to pass THAT.

Hi Neil. Thanks again for adding good comments and links to the conversation.

Hello? I am a six grader. For my science project, I am researching about the kakapos. i found most of the things I need, except for the life cycles of the kakapos and the ecological role in the nature. I know that they live for 60 to 95 years, but that is all I can find.

Also, aren't they very ingenious? They build their bowl near a rock or a stream, so when they scream, the sould gets louder!

Hello? I am a six grader. For my science project, I am researching about the kakapos. i found most of the things I need, except for the life cycles of the kakapos and the ecological role in the nature. I know that they live for 60 to 95 years, but that is all I can find.

Also, aren't they very ingenious? They build their bowl near a rock or a stream, so when they scream, the sould gets louder!

Hello? I am a six grader. For my science project, I am researching about the kakapos. i found most of the things I need, except for the life cycles of the kakapos and the ecological role in the nature. I know that they live for 60 to 95 years, but that is all I can find.

Also, aren't they very ingenious? They build their bowl near a rock or a stream, so when they scream, the sould gets louder!

Hello? I am a six grader. For my science project, I am researching about the kakapos. i found most of the things I need, except for the life cycles of the kakapos and the ecological role in the nature. I know that they live for 60 to 95 years, but that is all I can find.

Also, aren't they very ingenious? They build their bowl near a rock or a stream, so when they scream, the sould gets louder!

Hello? I am a six grader. For my science project, I am researching about the kakapos. i found most of the things I need, except for the life cycles of the kakapos and the ecological role in the nature. I know that they live for 60 to 95 years, but that is all I can find.

Also, aren't they very ingenious? They build their bowl near a rock or a stream, so when they scream, the sould gets louder!

Hello? I am a six grader. For my science project, I am researching about the kakapos. i found most of the things I need, except for the life cycles of the kakapos and the ecological role in the nature. I know that they live for 60 to 95 years, but that is all I can find.

Also, aren't they very ingenious? They build their bowl near a rock or a stream, so when they scream, the sould gets louder!

It is indeed sad, but hopefully one day these species will be able to survive on their own once more. Kakapo numbers are steadily increased, and since their island habitats are virturally the wild, once the gene pool is larger and as long as the islands remain predator free, then they could happily be left to their own devices.

I was watching a documentary on Hawaii a year or so ago and there was a chap there who had taken it upon himself to artifically inseminate a particularly rare endemic flower. It was restricted to high, dangerous cliffs on one of the Hawaiian islands and had previously been fertilised by a particular species of bird or insect (probably bird) that had now gone extinct. This chap was abseiling down cliffs to fertilise the flowers so that they could seed. This struck me as valiant, but ultimately pointless - since there was no way the original polinator was coming back and this entire species was basically being perpetuated by this one man. And what if he got sick, injured or just too old? Would someone else have to take up the reins?

But it is always the risk of anything being kept in captivity and breed - what will happen to it in the end? There's nowhere to return it to in many cases, and even if you did release it back into the wild where it once was found, the ecosystem would have changed to fill the gap that species left and bringing it back could throw a different species into decline.

Not that I think we shouldn't help the animals. Just that when I think about it too hard it makes me cold inside.

Its a great pleasure reading your post.Its full of information I am looking for and I love to post a comment that "The content of your post is awesome Great work.

Post a Comment

<< Home