Yes, I do recall my

promise not to turn this into a music review blog, but I'm sorry...I just can't help myself; within this meager chest beats the heart of a rock critic. The summer concert season has begun, and I'm going to completely indulge myself with this post, so you might consider giving the rest of it a pass and looking instead at some

dirty pictures.

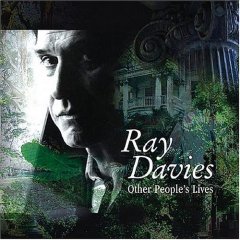

All summer long, the Salt Lake Arts Council sponsors a free concert each Thursday at a downtown park. This year's series debuted last night in neo-hippie splendor with Hot Buttered Rum and Michael Franti and Spearhead. Next week's lineup of Martin Sexton and David Lindley should be even better, but it's tonight's Ray Davies concert that got my fingers typing. I never thought I'd get to see the leader of the Kinks play an intimate bar venue. What's bad for him is good for me. I expect Michael Jackson will be playing the same club soon, and can only hope that one day David Bowie's career will hit a similar slump.

Davies was the singer, rhythm guitarist and primary songwriter for what was surely the most under appreciated of the “British invasion” bands, from their inception in 1964 through their final recording, Phobia, in 1993. Since then, though, he has been uncharacteristically silent, save for the 1998 release of

The Storyteller, an edited version of his touring spoken word/music performance of the same name, and last year's ep

Thanksgiving Day. Earlier this year he released his first full-length studio cd (if you don't count the soundtrack from his 1983 BBC television play

Return to Waterloo). Other Peoples' Lives was the latest of four cds from the past year or so from long-silent favorite artists. It's a collection of 13 songs that range from good all the way up. Davies has always used the same formula, taking blues, doo-wop, calypso, and other American idioms and forging from them well-crafted pop songs that are quintessentially British. The real standout on the new recording is

Next Door Neighbor, which is the kind of song Davies always did best, a critique of middle-class life without a trace of meanness, but with humor and sympathy for his protagonists. Davies was always capable of writing clever lyrics and wonderful melodies, but his greatest genius was in his delivery. No voice ever dripped more with sincerity. The sweetness of his tone always combined with an intonation that was off just enough to bring him to earth—he always sounded like a next-door neighbor. It's a rare quality that no one else I can think of, except maybe Mama Cass, could equal. With time, Davies' voice has only improved, and it shines throughout this recording, which is Ray at his best. He can still knock off an amazingly simple and beautiful melody like he does in Is There Life After Breakfast? In the title track,

Other Peoples' Lives, he blasts gossip journalism, again with more humor than hostility. The song benefits greatly by wonderful accompanying vocals by Afro Medusa's Isabel Fructuoso. The album's only weakness is the noticeable lack of Kinks lead guitarist Dave Davies. There's nothing wrong with Ray's guitar playing, but it lacks the raw power of his younger brother. The combination of Ray the sweet but sarcastic balladeer and Dave the power rocker was always one of their unique charms. Without that hard edge, some of the arrangements on

Other Peoples' Lives sound kind of square, more like Blur, or some of the other newer pop artists that started out by emulating Ray.

In early November, 12 years after her last recording, Kate Bush released

Aerial, a double cd set, and only her eighth studio release since Pink Floyd guitarist David Gilmour discovered the precocious teenager in the mid-seventies. Her first single release, Wuthering Heights, was a big international hit, changing her life forever. Her first two albums showed an extraordinarily talented young woman who played the piano well and wrote good songs that were literate and romantic. By the time of her third recording,

Never Forever, The 22-year-old Bush was controlling her own production. This was our first glimpse of the mature artist, as skilled and smart at arranging and producing as she was at composing. Since then she has been anything but prolific, but each recording has been a treasure, evoking powerful, often dark and disturbing moods. Even 1989's

The Sensual World, which in my estimation is her weakest work, is a beautiful album that includes some of her best singing. Bush's natural voice is quite thin, but over the years she has learned to use it to its fullest. Before even hearing her new cd, one is struck by its graphics. On the cover, an oscillogram of a birdsong appears like a landscape of rugged alien mountains jutting from a silent sea. Inside doves flutter, almost indistinguishable from windblown laundry on a clothesline. The bird imagery continues in the music, where she has taken recordings of European Blackbirds (

Turdus merulus) and Turtle Doves (

Streptopelia sp.) and written accompaniments for her piano and voice, with gorgeous results. Olivier Messiaen's use of bird songs in composition is no longer secure in its top position. The latter of

Aerial's two discs is a collection of songs that collectively paint a rich picture of a single uneventful day. It is a masterful composition that is nowhere ostentatious in its presentation. Disc number one consists of seven discreet songs, many of which have similarly small and pedestrian themes. Mrs. Bartolozzi deals with household chores in a manner no one else possibly could, and π is largely a recitation of the famous irrational number. A less confident composer would have tried to make up for the uninteresting lyrics, but Bush remains restrained and subdued, as she does throughout

Aerial. Only in

How To Be Invisible does she show a hint of the haunting darkness that I've always liked best in her work. She appears to be a happier person than she's ever been before; what's good for her is bad for me. The two discs are titled

A Sea of Honey and

A Sky of Honey—appropriate names, for this is Bush at her sweetest. Only in the third song,

Bertie, does her sweetness go over the top, though. It's a paean to her 8-year-old son that is sure to be the catalyst of many future fist-fights.

The third member of this quartet of recording artists is the least known. Despite having produced some 60 studio recordings in his career, Peter Hammill is far from a household name. He sang, played guitar and keys, and wrote virtually all the songs for Van der Graaf Generator, a British band named for a misspelling of the static electricity generator designed by Robert van de Graaff. VDGG survived from 1969 until 1977, during which time they seemed to break up every couple of years. Their best work came from the lineup of PH, David Jackson on woodwinds, Hugh Banton on keyboards and Guy Evans on drums. The latter two members were the virtuosi of the group, the first two played their instruments only adequately, but had unusual sensibilities that served the overall effect very well. Jackson attached pickups to the head joints of his instruments, and used a lot of effects. He often played two or three saxes at once, à la Rahsaan Roland Kirk. He was great fun to watch live, with three saxes and a flute hanging around his neck, and a tangled dragline of cords behind him. The lack of a bass player on their latter albums, Jackson's unique stylings, and Hammill's distinctive songwriting all combined to make VDGG sound like no other band, but it's Hammill's unusual singing that really puts the icing on a cake that most find completely unappetizing. Often referred to as “the Hendrix of the voice,” he uses a vast arsenal of sounds, from a ghostly, lugubrious falsetto to deep demonish rumblings, and everything in between. He interprets his own melodies in a very disorienting way, shifting from the root to the fifth, to the third, and back in a seemingly arbitrary fashion, often obscuring the melody almost completely. Hammill has always demanded a lot of his listeners. His best lyrics are brilliant, his worst are embarrassing. He is often pompous and self-absorbed. I don't think I'd like the man, but I've always loved his music. He started recording solo albums early in VDGG's career, often with the same lineup of musicians. To use painting metaphors, VDGG was Expressionism, while Hammill's solo work was Surrealism. In the time Kate Bush took to create a single record, Hammill was cranking out as many as nine or ten, many of them on labels he created himself. Over the past decade, his work has become too self-indulgent even for me, and I've only bought a couple of cds from that period. So it was with great excitement and curiosity that I ordered last year's new VDGG album,

Present. The old lineup of Hammill, Jackson, Banton and Evans is in true form, and it's really nice to hear from them again, even it's not their very best album. This, too, is a double cd, although there was no need to make it one. The second disc consists of over an hour of studio improvisation. It's interesting for obsessive fans, but eight minutes of this tacked onto the end of disc #1 would have been a better decision. As it is, that first disc contains six songs, one of them a passable instrumental by Jackson, three of them adequate Hammill songs, with the remaining two being the real reason to own the set.

Every Bloody Emperor is surely being sung to George Bush, and it's done so with a vitriol that's so melodramatic as to make it hilarious fun.

Nutter Alert is even a better ride. Old Peter hasn't rocked this hard since the early 80s. I wonder why not—he definitely still has it.

Last on the list is Brian Eno, who began as a member of the original Roxy Music in 1971, and played on their first two records before leaving to record four albums of his own quirky pop songs. These became increasingly interesting as he became better at manipulating sound textures. His beautiful

Another Green World from 1975 is a "desert island disc." After recording

Before and After Science in 1978, he abandoned songwriting in favor of working with soundscapes and collaborating with a veritable who's who of popular music. No musician less adept has worked with more musicians more adept, but it's not his chops, but his fertile artistic mind that has attracted the likes of Robert Fripp, Peter Gabriel, John Cale, John Cage, Hans Roedelius, Harold Budd, Laurie Anderson, David Byrne, etc., etc... His first soundscape album was the famous

Music For Airports, his first ambient project. The idea was to compose ignorable recordings to play in a specific space to create a mood. These recordings were typically created by playing loops of tape, and recording and re-recording repeating patterns. The tapes could be cut increasingly short for an accelerando effect, and Eno used many other ingenious low-tech devises to achieve his ends. For the past thirty years, he's recorded a great deal of ambient music, and produced a lot of records for various other artists, not to mention being involved in numerous projects having nothing to do with music, but for over a quarter century, until last year's

Another Day On Earth, he hasn't recorded any songs. I didn't know what to expect from this recording, but had I given it more thought, I should have expected exactly what it is: The same guy that recorded

Another Green World after 25 years of doing ambient music. The overall sound is colder and less imperative than his work from the 70s, but the melodies and lyrics, smart and simple, came obviously from the same mind. There is whimsy here, though sadly not to the Lewis Carrollian degree of, say,

Backwater from

Before and After Science, and much of it sounds like it could have come straight from that old vinyl, particularly

How Many Worlds, with its simple 2-chord structure and rudimentary piano accompaniment. This is a more minimalist work than any older Eno song albums, but oddly satisfying. The last cut, the disturbing

Bone Bomb, is the simplest, most powerful and most satisfying song of all. Like the previous three cds, this is not my favorite work by this artist, but it shows an intelligent, mature creator that has spent the past decade growing as an artist.

I don't think it's hyperbole to call my friend Frans Lanting the best nature photographer around; I don't know another who equals him. He and his wife Chris Eckstrom, a fine nature writer, have collaborated on many books and other projects, and over the past few years they've been focused on an undertaking of unprecedented ambition: a book on the history of life on earth.

I don't think it's hyperbole to call my friend Frans Lanting the best nature photographer around; I don't know another who equals him. He and his wife Chris Eckstrom, a fine nature writer, have collaborated on many books and other projects, and over the past few years they've been focused on an undertaking of unprecedented ambition: a book on the history of life on earth.