Tuesday, October 31, 2006

Thursday, October 26, 2006

Monday, October 23, 2006

PHOTOGRAPHY AND THE PAINTER, Part iii—A Personal Reflection

It's been a while since I put them up, so I reread the first two posts in this series to refresh my memory. The first was a brief description of the history of photography and painting, and the second a brief history of the Photorealist movement. With that basis, it's high time to deal with how photography has affected my own painting. I have nothing against Photorealism, but I bristle when the term is used to describe my work. Not only is the phrase usually used derogatorily to dismiss representational art as passé, it's a poor description of what I do.

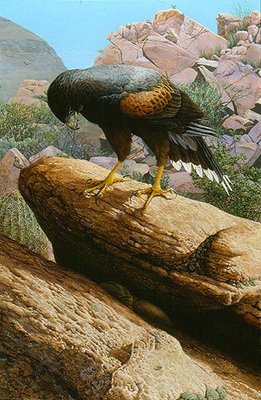

It's been a while since I put them up, so I reread the first two posts in this series to refresh my memory. The first was a brief description of the history of photography and painting, and the second a brief history of the Photorealist movement. With that basis, it's high time to deal with how photography has affected my own painting. I have nothing against Photorealism, but I bristle when the term is used to describe my work. Not only is the phrase usually used derogatorily to dismiss representational art as passé, it's a poor description of what I do. I've executed a few pieces that qualify as marginal Photorealism. The painting The Sunning Stone (above), an oil painting from 1988, is a sort of collage of three photos: two of Golden Eagles by Steve Chindgren, and one of a rock pedestal in Canyonlands National Park by Al Hartmann. This sort of stitching together of copied photos of subject and background is a hallmark of contemporary wildlife art, and, in the manner typical of my genre, I adjusted various aspects of color and composition to “improve” on the photographs, but otherwise relied completely on them to inform the painting. Compare another photoreliant painting, the more recent Yellow-Crowned Night Heron Portrait (right), with its photographic progenitor (left).

I've executed a few pieces that qualify as marginal Photorealism. The painting The Sunning Stone (above), an oil painting from 1988, is a sort of collage of three photos: two of Golden Eagles by Steve Chindgren, and one of a rock pedestal in Canyonlands National Park by Al Hartmann. This sort of stitching together of copied photos of subject and background is a hallmark of contemporary wildlife art, and, in the manner typical of my genre, I adjusted various aspects of color and composition to “improve” on the photographs, but otherwise relied completely on them to inform the painting. Compare another photoreliant painting, the more recent Yellow-Crowned Night Heron Portrait (right), with its photographic progenitor (left).

While executing paintings like these is a good discipline, I don't find the results terribly satisfying, and equate them with Rachmaninoff's daily playing of scales. As I mentioned in part ii, I find the distortion and exaggeration of subjects not lifted from photographs to be more “poetic” than photorealistic subjects. My own subjects fall far short of the poetry of Rembrandt's, as well as of my own objective, the rendering of somewhat distorted and “poetic” subjects in a highly realistic and detailed manner. An example can be seen in the painting above. Awakened by raindrops after a long, subterranean summer slumber, the Couch's Spadefoot Toad (Scaphiopus couchi) in Call of the Monsoon arches its back and squints its eyes in a manner more befitting a purring cat than an amphibian. The posture is physically possible, but is not one likely to be seen, much less photographed. Hopefully, the painting describes the spadefoot's motivation better than any photo could.

Likewise, the subject of Great Helmeted Hornbill executes a silly pirouette that no self-respecting wild bird would attempt, but the bird's posture, along with the painting's composition and point of view, all conspire to describe the difficulty of hoisting a one-pound bill casque aloft.

Likewise, the subject of Great Helmeted Hornbill executes a silly pirouette that no self-respecting wild bird would attempt, but the bird's posture, along with the painting's composition and point of view, all conspire to describe the difficulty of hoisting a one-pound bill casque aloft.

Don't let me leave an impression of contempt for photography as an element of the painter's toolbox. Rarely do I paint a piece without using it. In Instant of Opportunity, a pair of Emerald Toucanets chases a Spiny-headed Treefrog from a tree cavity. The postures of the subjects and the composition of the painting are as contrived as can be, and were all arrived at without the benefit of photographs. The anatomical structure was corrected using photographs, and many elements in the piece, including a bromeliad, berries, treeferns and many of the background trees were lifted directly from photographs I took in the Central American highlands. The various elements, some copied from sketches and photos, and some fudged, were combined in a composition where a centrally located X, formed by the two birds' bills, a branch, and a row of treefern crowns provides a fulcrum from which the frog propels himself.

Photographs can be used as simple storage devices for information, without actually copying them. To paint the houses in the little village of Convoy Through the Canopy, I used two photographs of rural Sango architecture I had taken in the Central African Republic (above). Although the painting is drawn from a totally different angle, it is still completely informed from the photographs, as are the surrounding banana and cocoyam crops. The completed triptych is shown below.

Photographs can be used as simple storage devices for information, without actually copying them. To paint the houses in the little village of Convoy Through the Canopy, I used two photographs of rural Sango architecture I had taken in the Central African Republic (above). Although the painting is drawn from a totally different angle, it is still completely informed from the photographs, as are the surrounding banana and cocoyam crops. The completed triptych is shown below.

Photographs are extremely useful for analyzing textures, particularly moving ones, like water. For the painting Table Mountain Ghost Frog I built and painted a simple sculpture, cemented it to a stone, and ran a garden hose over the whole thing to see how a thin film of fast-moving water would be distorted by a frog clinging to a stone. One of the 36 photos I took is shown, along with the finished painting.

Photographs are extremely useful for analyzing textures, particularly moving ones, like water. For the painting Table Mountain Ghost Frog I built and painted a simple sculpture, cemented it to a stone, and ran a garden hose over the whole thing to see how a thin film of fast-moving water would be distorted by a frog clinging to a stone. One of the 36 photos I took is shown, along with the finished painting.

I designed the composition of Black Skimmer a couple of years before painting it. While canoeing on Upper Myakka Lake, I watched a squadron of these birds skimming at close range, scrutinizing closely the wakes they left behind them. I was surprised by how narrow they were; much more so than the drawings I had made, but after watching them I wanted still more information. I painted the piece the following winter, and took camera and tripod to a neighborhood park, unseasonably dressed in cutoffs and sandals, and waded into the duck pond. I set my camera just above the water's surface, and shot a roll of pictures as I sliced the surface with a Persian kindjal sword. The visiting families seemed disturbed to see a seedy-looking man with a large weapon up to his hips in frozen duck shit, and I imagine my exit only barely preceded the arrival of the police, but the resulting photos provided an invaluable tool for finishing the piece.

_____________________

All photographs and paintings by CPBvK

Tuesday, October 17, 2006

A BIT OF BRAGGADOCIO

I hate to boast...well, that's not exactly true, but I do think it's usually inappropriate...even so, I'm going to make an exception just this once. My friends Wes and Rachelle Siegrist attended last Friday's opening of Art & the Animal at the Bennington Center for the Arts in Vermont. A&TA is the big annual member's exhibition of the Society of Animal Artists. Wes emailed me yesterday to let me know that my painting Harris' Hawk & Chuckwalla was awarded the Society's highest honor, the Award of Excellence. So to celebrate, I'll post this shameless little gallery of my five paintings that have received Awards of Excellence from the society: (UPDATE: the other recipients of this year's Award of Excellence are: Robert Bateman, Willem de Beer, Carrie Gantt Quade, Patricia Jackman, Jan Martin McGuire, Matthew Gray Palmer, Louise Peterson, John Pitcher, Ken Rowe, John Seerey-Lester and W. Leon White.)

I hate to boast...well, that's not exactly true, but I do think it's usually inappropriate...even so, I'm going to make an exception just this once. My friends Wes and Rachelle Siegrist attended last Friday's opening of Art & the Animal at the Bennington Center for the Arts in Vermont. A&TA is the big annual member's exhibition of the Society of Animal Artists. Wes emailed me yesterday to let me know that my painting Harris' Hawk & Chuckwalla was awarded the Society's highest honor, the Award of Excellence. So to celebrate, I'll post this shameless little gallery of my five paintings that have received Awards of Excellence from the society: (UPDATE: the other recipients of this year's Award of Excellence are: Robert Bateman, Willem de Beer, Carrie Gantt Quade, Patricia Jackman, Jan Martin McGuire, Matthew Gray Palmer, Louise Peterson, John Pitcher, Ken Rowe, John Seerey-Lester and W. Leon White.)

2006: HARRIS' HAWK & CHUCKWALLA

Harris' Hawk (Parabuteo unicinctus) is a unique raptor species of the American tropics. Normally shunning thick jungles, it haunts llanos, chaco, chaparral and scrub forest in the drier parts of that region, ranging as far north as the southern tip of Nevada. Fast and powerful, this social bird feeds on a variety of prey, from rabbits and ducks to reptiles like the Chuckwalla (Sauromalus obesus), here seen engaged in its typical elusive tactic of sliding into a rock crevice and inflating its body. Incidental subjects in this painting include a Compass Barrel Cactus (Ferocactus cylindraceus), honey ants (Myrmecosus sp.), Desert Spiny Lizard (Sceloporus magister), Turkey Vulture (Cathartes aura), and Costa's Hummingbird (Calypte costae).

2004: NORTHERN CACOMISTLE

One of two members of a genus of long-tailed, agile carnivores, the northern cacomistle (Bassariscus astutus) is distributed in the western United States and Mexico. Like it's relative the raccoon, its range has expanded during the twentieth century, and now stretches as far east as Ohio and Alabama. Capable of exploiting a multitude of habitats, it is still most typically a creature of rocky terrain, scrambling about sheer cliffs with amazing dexterity. This nocturnal animal is only rarely abroad in daylight. It is usually only in the springtime that it habitually basks in the early morning sunlight before bedding down for the day. In Utah I associate the cacomistle with the sandstone desert of the Colorado Plateau. Incidental creatures in this piece are a side-blotched lizard (Uta stansburiana) and a hairy scorpion (Hadrurus sp.).

1997: ORANG-UTAN & ASIAN ELEPHANTS

This painting takes a vertical cross-section from a Sumatran rainforest, exposing a massive old male orang-utan (Pongo pygmaeus) observing a procession of elephants (Elephas maximus) coursing a trail beneath him. The northern Sumatran province of Acch is the last remaining stronghold of wild orangs on that island. They enjoy much larger distribution on Borneo, the other island that still harbors these strange and beautiful apes. The word "orang-utan" means "forest man" in Malay, and the Malay people traditionally considered them to be a different type of human, as did the the Dayaks of Borneo, who were said to explain their failure to speak as a ruse to avoid having to work. Adult orags associate with others of their kind temporarily as families, but are ordinarily quite solitary -- far more so than any other large primate. They spend most of their days carefully picking their way across the canopy, following the ripening of figs, durians and other fruits which make up the great bulk of their diet. Elephants occur on both Borneo and Sumatra, a fact that has long puzzled biogeographers, many of whom suspected their introduction by man centuries ago. Recent observations have confirmed that the creatures are capable of making such a trip by their own agency. Incidental animals in this painting include: greater racket-tailed drongos (Dicrurus paradiseus), red-throated barbet (Megalaima mystacophanos), crested lizard (Bronchocela hayeki), and birdwing butterfly (Troides sp.).

1996: OPTIMISM—ALLIGATOR SNAPPING TURTLE & PIG FROG

The Mississippi drainage system's Alligator Snapping Turtle (Macrochelys teminckii) is one of the world's largest freshwater turtles, capable of attaining weights in excess of 200 pounds. The oldest and heaviest individuals have been collected at the northern extremes of the species' range, causing some to speculate that old turtles prefer to orient themselves upstream and tend to creep north. I enjoy painting situations from a viewpoint completely unnatural to the human eye. When I'm capturing frogs, deep water provides them sanctuary, and I try to prevent their reaching it. I'm always aware that the situation is reversed from the point of view of the aquatic carnivore.

1994: GRIPPING TAIL—YELLOW BABOON & WHITE-THROATED MONITOR

I first drew a monkey pulling a large lizard by the tail at around age seven and revisited the concept a couple of times before "getting it right" with this piece some thirty years later, set in south-central Africa, in which the subjects are a yellow baboon (Papio cynocephalus) and a white-throated monitor (Varanus albigularis). As with most of my work, this situation is one that I've never seen, but as far as I can figure is perfectly plausible. I tried to design the piece so as to build a literal tension between the protagonists while imparting a motivation to them. The monitor's struggle against the tugging monkey cancels his own simultaneous effort to swing around and face his tormentor, creating a static tension emphasized by the lizard's fingers scraping through the sand. The baboon's air is much more placid: curious but apprehensive. Her cocked head and pigeon-toed stance confirm this. The line describing the tension runs from the curved lizard, through the straight line of tail and arm, ending in the monkey's kinked tail, which in turn is echoed in the shapes of the acacia suckers behind her. Elsewhere on the ground is a locust of the family Acrididae and an unidentified windscorpion (order Solpugida). The title "Gripping Tail" was suggested by conceptual artist Andrew Krasnow.

Monday, October 16, 2006

BILL BURNHAM 1947-2006

Bill Burnham, long-time president of the Peregrine Fund, died today of brain cancer. Bill's experience with birds of prey extended over 44 years, and led him around the world. He authored more than 90 scientific papers and articles, and one book, A Fascination with Falcons. Together, these various publications reflect his diverse interests in raptors, general science, and conservation, from captive breeding and egg physiology to raptor ecology and species restoration. In addition, Bill edited The Peregrine Fund's publications and web site, and co-edited the book Return of the Peregrine which chronicled the restoration of the Peregrine Falcon in North America and its de-listing from the Endangered Species List in 1999.

Bill Burnham, long-time president of the Peregrine Fund, died today of brain cancer. Bill's experience with birds of prey extended over 44 years, and led him around the world. He authored more than 90 scientific papers and articles, and one book, A Fascination with Falcons. Together, these various publications reflect his diverse interests in raptors, general science, and conservation, from captive breeding and egg physiology to raptor ecology and species restoration. In addition, Bill edited The Peregrine Fund's publications and web site, and co-edited the book Return of the Peregrine which chronicled the restoration of the Peregrine Falcon in North America and its de-listing from the Endangered Species List in 1999. During Bill's tenure as President of The Peregrine Fund, he focused on the continued expansion and evolution of the organization both nationally and internationally, beginning with construction of the World Center for Birds of Prey in Boise, Idaho, followed in 1986 by the establishment of The Archives of Falconry and the construction of a building specifically designed to house and breed tropical raptors (Tropical Raptor Building). Two years later, he co-founded the Maya Project in Guatemala and Belize which worked with more than 24 different raptors over a 10-year period of field work. In 1990 a field station was built in Madagascar and work began on endangered birds there; the following year the program expanded to the African mainland. Bill oversaw expansion of the education program with the construction of the Velma Morrison Interpretive Center in 1992, greatly increasing the number of annual visitors. Starting in 1993, a major program was initiated to breed in captivity and then release California Condors into the Grand Canyon, Arizona, in order to establish a wild population. This program required the construction of three buildings in Boise, as well as a field station in Arizona over the following 13 years. Additionally, large scale releases of Aplomado Falcons began in south Texas, with further releases in west Texas and New Mexico in later years. Facilities were constructed on two islands in Hawaii to work with rare and endangered Hawaiian birds; a program which was later passed to the Zoological Society of San Diego. In 1997 the High Arctic Institute was established and a field station opened at Thule Air Base, northwest Greenland, to provide a more secure base for the work Bill had been doing in Greenland since 1972. Work in the Neotropics was formalized with the establishment of Fondo Peregrino-Panama in 2000, and the construction of the Neotropical Raptor Center followed shortly after in 2001. In 2002 a long-term goal was realized with the construction of the Gerald D. and Kathryn S. Herrick Collections Building at the World Center in Boise, providing a long-term home for an extensive and ever growing library, egg and specimen collection, and The Archives of Falconry.

In addition to his work with The Peregrine Fund, Bill also attempted to influence conservation and government policy regarding the environment whenever possible. He was appointed by Secretary of the Interior Lujan to the National Public Lands Advisory Council, served as a trustee on the Boise State University Foundation, as a conflict mediator and then member of the Bureau of Land Management's Oversight Committee for the Snake River Birds of Prey Area, on the council for the multi-agency and university Raptor Research and Technical Assistance Center, on the Board of the North American Raptor Breeders' Association, on the Advisory Board of the Walt Disney Company's Animal Kingdom, as an advisor to the Philippine Government on science and conservation for the Philippine Eagle, and as a Board member of the Philippine Eagle Foundation, Inc. Additionally, Bill advised on birds of prey and conservation in various other functions nationally and internationally. He was a fellow member of The Arctic Institute of North America and of The Explorers Club. He received the Explorers Club's Champion of Conservation Award in 2004 and was awarded the Zoological Society of San Diego's prestigious Conservation Medal in 2006. In the several years before his death, Bill dedicated a significant amount of his time to the re-writing of the Endangered Species Act, working with lawmakers and testifying before both House and Senate subcommittees in an attempt to add language to make the Act more user-friendly and effective for conservation organizations.

The long-term effects of Bill's influence on conservation through the activities of The Peregrine Fund have yet to be felt. Bill strongly believed that education of local individuals in the countries in which The Peregrine Fund worked was a critical component of conservation, leading to The Peregrine Fund supporting students from Mongolia to Madagascar, with more than 20 PhDs, 53 MScs, and countless other BS and high school diplomas earned. During his tenure over 2,000 Peregrine Falcons, 1,250 Aplomado Falcons, 93 California Condors, and 47 Harpy Eagles were produced in captivity and released into the wild. Highlights included the de-listing of the Peregrine Falcon from the Endangered Species List in 1999 and the first wild-produced California Condor fledging in the Grand Canyon in November 2003. What was perhaps Bill's greatest accomplishment, and the one he was the most proud of, was the bringing together of the world-changing staff, Board of Directors, collaborators, and members that make The Peregrine Fund what it is today and have made all of the before-mentioned results possible. Bill is survived by his wife Pat and son Kurt, a PhD candidate in ornithology at Oxford.

A memorial service will be held at the World Center for Birds of Prey in an outdoor tented structure on 21 October 2006 at 2:00 in the afternoon, followed by a reception inside the Velma Morrison Interpretive Center. Those wishing may contribute to The Peregrine Fund's endowment so that Bill's efforts can be continued in perpetuity. Donations should be made directly to The Peregrine Fund and will be split equally between the general endowment for The Peregrine Fund and the endowment for The Archives of Falconry.

Friday, October 13, 2006

SPEAK NO WEEVIL

They're celebrating National Weevil Day up in Canada right now, and although I'm situated several hundred miles shy of the 49th parallel, I can think of nothing better to do than briefly celebrate the world's largest animal family, Curculionidae.

They're celebrating National Weevil Day up in Canada right now, and although I'm situated several hundred miles shy of the 49th parallel, I can think of nothing better to do than briefly celebrate the world's largest animal family, Curculionidae.No one knows how many weevil species there are, least of all me, but they number well over 40,000. Mostly tiny insects, their elongated snouts bear a pair of elbowed, club-tipped antennae that give them a distinctive, rather comical look. The snout is tipped with chewing mouthparts that shred the vegetable matter these beetles subsist on. Weevil larvae tend to be cryptic borers and miners. Most weevils are specific feeders, and many rely solely upon a single plant species. Most host plants are woody, and weevils are important pests of a great many human crops, including many species of timber, nut and fruit trees, alfalfa, peppers, potatoes, bananas, and, of course, the most famous weevil of all, Anthonomus grandis, the Cotton Boll Weevil. Heavy weevil infestations usually only occur in monocrop agricultural settings, or in plants that have been stressed by a secondary factor. Some weevil species are beneficial to humans, and a few have been put to use to control invasive plants, including Neochetina spp., which feed on Water Hyacinth (Eichhornia crassipes), Hadroplontus litura, which has long been used to control Canada Thistle (Cirsium arvense), and weevils of the Genus Coniatus, an enemy of the most obnoxious invasive plant of the western American deserts, the Tamarisk (Tamarix spp.).

Although most curculionids are drab and only a millimeter or two in length, a few of them are quite spectacular. Among these are the two New Guinean genera Gymnopholus and Eupholus, which are large and colored in shades of beautiful reds, blues and greens. Bennett's Painted Weevil (Eupholus bennetti), depicted in the painting above, at an inch in length, is one of the world's largest and most handsome weevils. Another notable species is Tracheophorus giraffa, the Madagascan Giraffe Weevil, named for the extremely elongated prothorax and head of the male, which is used to roll a leaf chamber in which the female lays a single egg.

Maintaining the spirit of yesterday's post, the weevil genus Zyzzyva is often cited as the very last genus, alphabetically, although both the wasp genus Zyzzyx and the hydrozoan genus Zyzzyzus narrowly beat it.

Happy Birthday, Weevil!

_____________________

upper: BENNETT'S PAINTED WEEVIL (2003) acrylic 5" x 8"

lower: Photograph of Tracheophorus giraffa taken by CPBvK north of Antananarivo, Madagascar in 1997

Thursday, October 12, 2006

CAENORHABDITIS, HEARNORHABDITIS

Just a couple of days ago, a news report announced the discovery of a new Brush-finch (top photo) in Colombia, about a month after a similar story reported the naming of Liocichla bugunorum, a new babbler (bottom) found in India. The Colombian bird, christened Atlapetes latinuchus yariguerum, is not actually a new species, but a subspecies of the Yellow-breasted Brush-finch. One interesting aspect of these two discoveries was the nature of the holotypes that were collected. Protocol demands that before a taxon is named, the specimen from which the description is taken must be collected, so that a model of comparison exists. In these two new cases, nothing more than photographs and DNA were retained as type specimens (although one of two captured A. l. yaguerum died before it could be released, and could presumably serve as a traditional type specimen). Should this new standard be accepted, it will obviate the need to sacrifice a precious member of a rare species. Still, the lack of a physical standard for the taxon will represent a scientific deficiency until computer modeling technology can fully replace study skins.

Just a couple of days ago, a news report announced the discovery of a new Brush-finch (top photo) in Colombia, about a month after a similar story reported the naming of Liocichla bugunorum, a new babbler (bottom) found in India. The Colombian bird, christened Atlapetes latinuchus yariguerum, is not actually a new species, but a subspecies of the Yellow-breasted Brush-finch. One interesting aspect of these two discoveries was the nature of the holotypes that were collected. Protocol demands that before a taxon is named, the specimen from which the description is taken must be collected, so that a model of comparison exists. In these two new cases, nothing more than photographs and DNA were retained as type specimens (although one of two captured A. l. yaguerum died before it could be released, and could presumably serve as a traditional type specimen). Should this new standard be accepted, it will obviate the need to sacrifice a precious member of a rare species. Still, the lack of a physical standard for the taxon will represent a scientific deficiency until computer modeling technology can fully replace study skins.A new bird is usually described every year or so, but species of simpler creatures turn up with greater regularity. My friend Wayne Davis literally discovered a new species in his own back yard earlier this summer. Wayne's discovery belongs to the genus Caenorhabditis, the nematode group that includes the famous millimeter-long worm C. elegans, used in laboratory research for four decades. Wayne tells me that the most common question he fields, concerning his discovery, is the first one I asked: “What's it going to be called?” Binomial scientific names often involve entertaining stories, but Wayne's obligatory answer was a disappointing anticlimax: “Species #6.”

The nematode community decided that Sydney Brenner, whose pioneering molecular studies in 1965 established C. elegans as an ideal lab animal, should be honored by naming a Caenorhabditis species for him. After the decision was made, the first three species discovered were deemed too distant from C. elegans to bear his name, so they were given numbers, until an appropriate species could be found and named. Species #4 was closer to C. elegans, and it was decided that it should be named for Brenner, but the description is being done by an elderly German nematologist who communicates solely via snail-mail, and is in no rush to complete the job. In the meantime, subsequent discoveries are being given numbers until the issue is resolved. Wayne and his colleague, Michael Alion, who is describing the worm, also worry about some century-old Caenorhabditis species named before the days of electric freezers or DNA sequencing. The descriptions of long-ago discarded holotypes based solely on morphometric studies are useless today as standards, since morphometry can vary widely within a single species. These types can hardly be seen as representative of valid species, yet the names have not been deemed obsolete (as they probably should be), and one could possibly be given precedence over Michael's.

While the ball is in someone else's court, Wayne and Michael are mulling over possible names like expectant parents. They could name it for Salt Lake City, or figure out the Latin term for “rotten apricot,” the substrate from which they isolated the worm, or they could look in any number of other directions. In 2000, fellow Salt Laker Scott Sampson found the remains of a new theropod dinosaur on Madagascar. His party had noticed that they found better fossils while listening to Dire Straits, so Sampson christened the dinosaur Masiakasaurus knopfleri for the band's leader. Some news accounts called M. knopfleri the first species named for a musician, but that's far from the truth. Mozart, Beethoven and Chopin have all given their names to species. A goby genus and a species of snail, spider and jellyfish (not to mention two asteroids) were named for Frank Zappa. Australian paleontologist Greg Edgecombe has named many trilobites for musicians, including Avalanchurus lennoni, A. starri, Struszia mccartneyi and S. harrisoni for the Beatles, Mackenziurus johnnyi, M. joeyi, M. deedeei, and M. ceejayi for the Ramones, Aegrotocatellus jaggeri and Perirehaedulus richardsi for members of the Rolling Stones, and Arcticalymene viciousi, A rotteni, A. jonesi, A cooki and A. matlocki for the Sex Pistols. Another favorite Edgecombe trilobite taxon is the genus Aegrotocatellus (Latin for “sick puppy"). Cartoonist Gary Larson was honored with the naming of the beetle genus Garylarsonus. When the owl louse Strigiphilus garylarsoni was described, he quipped, “I considered this an extreme honor. Besides, I knew no one was going to write and ask to name a new species of swan after me.” In the 1930s, ornithologist Col. Richard Meinertzhagen named well over a dozen species and subspecies of birds “theresae,” after Theresa Clay, a “confidante” 33 years younger than himself.

These are just a few interesting stories of scientific binomials. In the future I will probably devote a post to more of them, but for now I'll close this one with my favorite, a small catfish found in the Purus River in Brazil. It was described in 1980 by Nijssen and Isbrücker, who were lobbied hard by the collector, who insisted the fish should be named after him. After much consideration, Nijssen and Isbrücker honored his request, and named the fish Corydoras narcissus.

_____________________

upper: Photographs swiped from National Geographic Society

lower: HARRIS' ROSE BEETLE (1997) acrylic 3" x 5"